Nancy Pearcey has written a book on the masculinity crisis entitled The Toxic War on Masculinity. The title makes clear her basic perspective: it is not masculinity, but the war on masculinity, that is truly toxic. Masculinity is the original software God programmed into man. It has now been infected with a virus, but the original coding — which can be recovered by divine grace — is intrinsically good and necessary to human flourishing. I think Percey's book is loaded with useful information — it is perhaps the best defense of complementarianism written since the inception of the movement (though she does not use that label). I also think the book will make absolutely no difference in the current debates over manhood and it will not really help young men solve the dilemmas they face in our culture today. Young men seeking inspiration and direction in cultivating full-orbed masculinity will have to look elsewhere. This book identifies a major problem — our culture's toxic war on good masculinity — but it does not show the way to win that war. The failings of Pearcey’s book are really those of the complementation movement more broadly. Pearcey gives, at best, a very partial picture of what masculinity should look like.

If the book is so good in so many ways, why won’t it help solve the crisis? Why won’t it end the toxic war on masculinity? I hope that will become clear as I go. Pearcey is a superb researcher and all her skills are on display in this volume. Her previous work, Love Thy Body is one of the best books I have read over the last 5 or 10 years. While I did not find this book to be as compelling overall, it's still worth reading and engaging. But as indicated already, it comes up short because of some significant blind spots.

I could write several thousand words about what I liked in this book. Here are some key highlights:

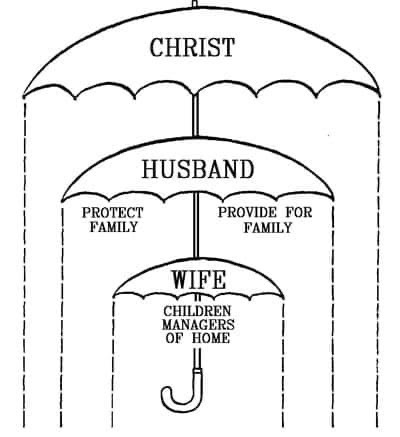

- Pearcey sets out to defend masculinity in general and evangelical men in particular. Since evangelical men unfairly get a bad rap, this is especially appreciated. She understands that many men have felt that they had to choose between their masculinity and their faith, as if both the modern world and the modern church told men, “You can be a man or a Christian, but you cannot be both" (118). As an apologetic work, her book largely succeeds in defending masculinity against this false choice. Relying primarily on anecdotes (usually in the form of quotations) and sociological data, Pearcey shows that not only are evangelical men generally good men, they are the best men in our culture. Women married to these men have the highest levels of satisfaction in our culture; the children of these men have best shot at thriving into adulthood; and in many ways these men are the hidden backbone of our society since they are dependable, resourceful, and diligent. Vibrant Christian faith (primarily marked by regular church attendance/participation) is key to being a good man. When the data is carefully considered, we find that the charges brought against evangelical men, e.g., that a complementrian view of headship is linked with abuse and misogyny, are actually slanderous. Christian faith makes men better men; it transforms them into “soft patriarchs,” to use Brad Wilcox’s term, and these soft patriarchs are generally quite adept at caring for their wives and children.

- Interestingly, Pearcey shows that nominally Christian men are actually among the worst of men when it comes to how they treat women. Perhaps this is because they imbibe the rhetoric of headship, but not the actual biblical content that fills it out. In other words, it is dangerous to tell men they are “in charge” unless that is fleshed out in a Christ-like way, per Ephesians 5. This leads to an important conclusion: While it seems that patriarchy is an inescapable concept, since virtually every known society in history has been led and ruled primarily by men, not all patriarchies are good. It is a fact that men will rule, but it not a given that they will rule well. This is precisely why Pearcey’s book is so necessary: the war on masculinity is toxic because it makes men worse instead of calling on them and equipping them to do better. The need of the hour is not to “smash the patriarchy,” but to build better patriarchs. A summation: Men who attend church regularly “are more loving to their wives and more emotionally engaged with their children than any other group in America. They are the least likely to divorce and they have the lowest levels of domestic abuse and violence.” By contrast, nominal Christian men “report the highest rate of [abuse] of any group — even higher than secular couples."

- Pearcey distinguishes two scripts for masculinity, the “good man” script and the “real man” script. Being a good man is defined in terms of honor, duty, and integrity. Being a real man is all too often defined in terms of socioeconomic status and sexual conquests. In Pearcey’s view, these two visions are masculinity are very much at odds; one represents a moral version masculinity, the other is masculinity cut loose from the restraints of faith and family. Some might wonder how Pearcey’s categories map onto other distinctions, e.g., is the good man a “beta male” while a “real man” is an alpha male? I’ll tackle this in a bit, and seek to correct the way Pearcey defines and relates the two scripts. But Pearcey is no doubt right that there are competing scripts for masculinity today and getting the script right is crucial to restoring cultural sanity. Men are desperate for a roadmap to true masculinity; let’s give them one.

- Pearcey seeks to do justice to the biological differences between the sexes. I do not think she captures everything that needs to be said here, but her discussion on p. 31 is at least a start. Biological realism was a theme in Love Thy Body, so interested readers could also look at that book. However, it is questionable whether or not Pearcey sufficiently follows through on the meaning and implications of these biological differences. I’ll circle back to her deficient view of nature/creational design below. For now, note that affirming biological differences between men and women is good and necessary, but not sufficient. The psychological and intellectual differences between men and women are arguably even greater than the physical differences.

- Pearcey has many good and helpful things to say about the crisis of fatherlessness in our culture today (35ff, 139f, 191fff). While a great deal of work has been done on the biological changes that take place in a woman when she gives birth, Pearcey rightly calls attention to the fact that having a newborn changes the father as well (202ff, 207). This is a crucial feature in Pearcey’s book that corrects many conservative and Christians who have written on manhood/fatherhood the last few decades (e.g., George Gilder, Graham Stanton): There has been a tendency to say that while motherhood is natural (because of the mother’s innate and biological bond with the child), fatherhood is merely cultural. But this is false. Fathers have biochemical bonds with their infants just as much as mothers. Men are designed for fatherhood every bit as much as women are designed for motherhood. We do not impose fatherhood on men, by custom or law; rather fatherhood is natural, and custom and law are useful in reinforcing nature since we are prone to rebel against it. Pearecy is right, then, that “The most important long-term solution to toxic male behavior…is to strengthen men’s commitment to fatherhood.” True masculinity will be family oriented, and it is so by divine design, not because of social construction. The war on masculinity is toxic because it is a war on fathers, and fatherlessness is the most destructive social phenomenon in our society today: "The sheer number of social problems exhibited by fatherless boys gives the lie to the idea that masculinity is toxic. If that were true, why is it that the greatest risk factor for violence and antisocial behavior in boys is growing up without a father’s presence in their lives?”

- Pearcey opens the book talking about her own experience with an abusive father. She ends the book by circling back around to the topic of abuse, including the story of her own healing. While there are some holes in her discussion of abuse that need to be filled in, overall she does a very good job with a difficult topic. She rightly points out that many in the church have not really understood how to deal with abuse and provides many helpful reminders. e.g., counsel that we might normally give to a wife in a struggling marriage (“submit to him more, be kinder to him, look your best, be sexually available for him”) actually backfires in abusive marriages (256). Sins of abuse (or, more accurately, oppression) need to be distinguished from run-of-the-mill “normal” marital sins. Churches actually err on both sides, sometimes stretching the definition of abuse so widely that marriages are terminated with divorce even though biblical grounds are lacking; at other times, churches have pressured victimized spouses to stay in marriages where they should have been granted biblical grounds for divorce by a church court. Marriage is a “for better or worse” covenant; just because a marriage is difficult does not mean it can be terminated with divorce (cf. 1 Peter 3). At the same time, God does not require a spouse to stay in a marriage where they are being repeatedly physically harmed or endangered (cf. Exodus 21:10-11; Deut. 23:15-16). Over the years, as a pastor, I have seen several cases where a spouse had grounds and probably should have sought for divorce, but did not; and I have seen other cases where it was obvious a spouse was looking for a way out of a hard marriage even though they did not have biblical warrant to seek a divorce. Pearcey rightly acknowledges that sometimes women can be the abusers (though interestingly, she does not have much advice to offer men who are on the receiving end of abuse). Pearcey also points out that seeking to appease bullies by giving them what they want almost always makes things worse rather than better; the only way to deal with a bully to stand up to him. Since abusers are bullies, attempts at placating them are not a way forward (256f). Pearcey, following the biblical example of Abigail in 1 Samuel and the teaching of Augustine, points out that husbands who abuse their wives forfeit their right to expect her submission (257f, 266). While she does not discuss some of the key biblical texts that bear on the issue of abuse as grounds for divorce (e.g., Exodus 21:10-11), her overall treatment is very useful and a step in the right direction.

Why did most women oppose women's suffrage? It was not out of 'indifference' or 'apathy.' Instead, it was because they understood clearly that universal suffrage implied a shift from the household to the individual as the basic unit of society. As one anti-suffrage group wrote in 1894, 'the household, not the individual, is the unit of the State, and the vast majority of women are represented by household suffrage.' Another anti-suffragist said the vote would 'strike at the family as the self-governing unit upon which the state is built.' Still another said it would, 'shift the basis of our government from the family as a unit to the individual.'

Why were women so concerned about a shift from the family to the individual as the unit of society? Because it struck a blow to the concept of male responsibility. For if society accepted that a man voted as solely an individual, then it no longer held him morally responsible for representing the common good of the entire household.

In short, women were concerned that universal suffrage would reduce men's sense of accountability for everyone in the household…The debate over universal suffrage illustrated a shift in political philosophy from the household to the individual as the basic unit of society.

Eventually, of course, women came around to supporting female suffrage. Why? The tide began to turn when the vote was expanded to universal male suffrage—that is, when men who were not responsible for a household were given the right to vote. At that point, the meaning of the vote changed. Men no longer voted as officeholders responsible for the common good of the household but only as individuals. Politics was now every man for himself.

And if the vote represented only individual interests, women concluded—quite logically—that they too needed to represent themselves. They could no longer count on the head of the household to represent their interests. Read these poignant words by Alice Henry, a leader in the Women's Trade Union League: Female suffrage is necessary, she said, because men, even good men, cannot be trusted to take care of women's interests.

In short, women's suffrage represented a tragic erosion of women's trust in men to take responsibility for the common good—especially women's good.

Amen.[I]f women were defined as the morally superior sex, responsible for instilling virtue their husbands, then in essence America was releasing men from responsibility to be virtuous…For the first time in history…women took men’s place as the custodians of communal virtue…Yet when the Bible calls men to spiritual leadership, it assumes that God has equipped men with the character traits needed for the task — both strength and empathy, both determination and gentleness. Instead of asking women to civilize men, a more biblical course would have been to challenge men to accept their responsibility before God for developing the full range of many virtues (112f).

Men do not find their true self by escaping relationships and riding off into the sunset like a lone ranger. They find their authentic manhood in their core relationships: to God, their wife, their children, their extended family. The phrase ‘be fruitful’ also means to build up the social institutions that historically grow out of the family [including] schools businesses, governments, charities, and community associations…The best strategy for men to validate their identity, then, is to roll up their sleeves and invest more deeply in their families and in creative work that builds up and benefits the human community. The cultural mandate summon up men’s drive to achieve, to accomplish, to have an impact (158).

As we might expect, “The nineteenth century strategy of giving women responsibility for taming men did not work. And despite what evolutionary psychologists say, it will not work today. Telling men that they must submit to what they perceive to be a feminine standard will only spur them to revolt” (173).Tell men they are naturally irresponsible brutes, captive to ancient caveman urges, and they will start acting like it. They will start treating marriage as an imposition that works against their true nature, a trap that constrains their free spirit. The results are exactly what we see today: too many young men refusing to grow up, avoiding the responsibilities of job and family…Negative definitions of masculinity have negative consequences (171).

Pearcey rightly detects that the trajectory of a feminized faith led straight to theological liberalism. Liberal theologians were mocked as “effeminate” and “sissies” and “little infidel preacherettes” for good reason. The “muscular Christian” movement tried to re-establish male responsibility; its proponents claimed,[S]ports programs are especially important for sending a message that the church honors male energy and physicality. Because of testosterone, men tend to be more physically active and competitive, and these are good gifts from God that should be validated. Team sports can also draw men to the church by fostering male friendship and camaraderie (179).

If God is going to win the country, he must do it through men…God is masculine God…The pulpit is the place for the strongest men we have…nothing emphasizes and exalts manliness, as does Christianity…no man is a man unless he is a Christian…[it is] a wicked, hellish, ungodly, satanic teaching that by nature men are not as good, that by nature women are …[more] inclined toward God and morality….Not a line in the Bible indicates that by nature men shouldn’t be required to be as godly as any woman, as pure in mind as any woman, as loving and kindly as any woman (183, 186).

Men will be drawn back to family life only when they realize that being a good husband and father is a manly thing to do; that paternal duty and compassion are not female standards imposed upon men but are integral to the male character as it was created by God. Men are intrinsically relational and they are happiness when they create rich, loving relationships, especially with their wives and children…Authentic masculinity is best achieved by embracing the responsibilities of mature manhood — becoming a deeply engaged husband and father…Honoring fathers will do more than any other single strategy to prevent toxic behavior in the next generation of men (192, 206).

Smug misandry has been box-office gold for Barbie, which delights in writing off men as hapless romantic partners, leering jerks, violent buffoons, and dimwitted tyrants who ought to let women run the world.Numerous studies have shown that both sexes care more about harms to women than to men. Men get punished more severely than women for the same crime, and crimes against women are punished more severely than crimes against men. Institutions openly discriminate against men in hiring and promotion policies—and a majority of men as well as women favor affirmative-action programs for women….

The education establishment has obsessed for decades about the shortage of women in some science and tech disciplines, but few worry about males badly trailing by just about every other academic measure from kindergarten through graduate school. By the time boys finish high school (if they do), they’re so far behind that many colleges lower admissions standards for males—a rare instance of pro-male discrimination, though it’s not motivated by a desire to help men. Admissions directors do it because many women are loath to attend a college if the gender ratio is too skewed.

Gender disparities generally matter only if they work against women. In computing its Global Gender Gap, the much-quoted annual report, the World Economic Forum has explicitly ignored male disadvantages: if men fare worse on a particular dimension, a country still gets a perfect score for equality on that measure. Prodded by the federal Title IX law banning sexual discrimination in schools, educators have concentrated on eliminating disparities in athletics but not in other extracurricular programs, which mostly skew female. The fact that there are now three female college students for every two males is of no concern to the White House Gender Policy Council. Its “National Strategy on Gender Equity and Equality” doesn’t even mention boys’ struggles in school, instead focusing exclusively on new ways to help female students get further ahead.

Women have been a majority of college graduates since 1982 and dominate by many other key measures…

Society tends to care for women while ignoring the plight of men:

[Women] not only live longer than men but also benefit from a higher share of federal funding for medical research. They’re much less likely to be fatally injured on the job or commit suicide. They receive the lion’s share of Social Security and other entitlement payments (while men pay the lion’s share of taxes). They decide how to spend most of the family income. Women initiate most divorces and are much likelier to win custody of the children. While men are ahead in some ways—politicians love to denounce the “gender pay gap” and the “glass ceiling” supposedly limiting women—these disparities have been shown to be largely, if not entirely, due to personal preferences and choices, not discrimination….

While the wage gap between men and women is a myth, bias in favor of hiring females is not a myth:

In 2016, the Australian national government launched a rigorous quest to combat its own misogyny. As part of its “Gender Equality Strategy,” it brought in Harvard economist Michael J. Hiscox to address a disparity in the government workforce: women held 59 percent of the jobs but only 49 percent of the executive positions...

The experiment produced an “unintended consequence,” as the researchers ruefully noted in their report, “Going Blind to See More Clearly.” When managers evaluated a résumé with a female name like Wendy Richards, they were more likely to shortlist it than if they saw that same résumé with no name. And they were less likely to shortlist it if the name was Gary Richards. Australia’s public servants were clearly guilty of bias against men—and that was just fine with the architects of the Gender Equality Strategy…In the real world, a full-time female worker over 25 in America earns 84 cents for every dollar a male earns, but even equalitarian researchers acknowledge that this gap is not due to overt sexual discrimination (illegal since the Equal Pay Act of 1963). It’s due mainly to men choosing higher-paying professions, like coding, instead of, say, teaching, and to the “motherhood penalty.” There’s no significant gender gap between childless singles in their twenties, but once they become parents, mothers tend to reduce their hours, switch to a lower-paying job with more flexibility, or drop out of the workforce. To equalitarians, these differences are the result of systemic sexism: gender stereotypes that discourage girls from seeking high-paying jobs and saddle them with an unfair share of child-care responsibilities….On average, women care more about “work-life balance” and finding a job that seems personally and socially meaningful—typically, one in a comfortable environment that involves working with people rather than things. Men prioritize making money, so they’re willing to take less appealing jobs—work that’s tedious, outdoors, dirty, dangerous—with longer, less predictable hours. The gender pay gap among graduates of elite business schools is due in significant part to their job choices. The male MBAs are likelier to take jobs in finance and consulting, whereas the women tend to choose lower-paying industries that are less competitive and less risky…..

Even dating, which is ultimately a zero sum game (since men and women either win or lose together), still presents a unique set of challenges for men in the modern world:

Women still prefer winners. They’re the pickier sex—on Tinder, they’re much likelier to swipe left—and they’re especially picky when it comes to a partner’s income, education, and professional accomplishments, as researchers have found in analyses of mate preferences, activity on dating websites, and patterns of marriage and divorce. Most American women still want a man who makes at least as much as they do—and wealthier women are more determined than less affluent women to find someone with a successful career.

While some traditional attitudes about wives’ roles have shifted, husbands are still typically expected to be breadwinners. An American couple is more likely to divorce if the husband lacks a full-time job, but the wife’s employment status doesn’t affect the odds. Studies of divorce rates in dozens of other countries have confirmed this peril to unemployed men, which comedian Chris Rock has also observed: “Fellows, if you lose your job, you’re going to lose your woman. That’s right. She may not leave the day you lose it, but the countdown has begun.”

The “metoo” movement is full of misandry. In saying this, I am not denying or excusing real cases of abuse that exist. Some men do terrible things to women and that should be addressed. But “metoo” has gone too far. “Metoo” has exaerbated the problem of bringing the sexes together — not only because it assumes men are guilty on the mere say-so of a woman (as if false accusations were impossible), but because it has made men fearful to approach women for fear of being labeled as creeps and getting stuck with an HR complaint (or worse):

Both sexes have also been hurt by the misandrist excesses of the #MeToo movement. With a few exceptions—like the actress Amber Heard, successfully sued by her husband, Johnny Depp—women who wreck men’s reputations and careers with false accusations suffer few consequences in the media or the courts. Police and prosecutors have routinely refused to act, even in clear cases of perjury, as Bettina Arndt has documented. These injustices, along with the draconian punishments and policies imposed by the (mainly female) managers of human resources, have instilled fear in workplaces, stifling office romances (which, in the past, frequently led to marriage) as well as valuable professional relationships. Most women still want men to make the first move in courtship, but who wants to risk being reported to HR for subjecting a colleague to “unwanted attention”? Even a purely professional meeting in private is risky if something innocent gets misconstrued—or falsely described by a hostile colleague exploiting the believe-all-women bias.

For young men today, the picture looks a lot closer to what Barbie envisions than many care to admit.

In a recent essay for the Washington Post, writer Christine Emba detailed the male problem at length, including her own anecdotal experience with male acquaintances who, she writes, lack friends, ambition, purpose, and even basic social skills. But this is not merely anecdotal: While older men still hold many high-level jobs, young men coming of age today demonstrate little promise of following in the same footsteps. Data from Pew Research Center show today’s 25-year-old women are just as likely as their predecessors in 1980 to work full time (both 61 percent) and more likely to be financially independent (56 percent versus 50 percent). By contrast, today’s 25-year-old men are significantly less likely to find full-time work than 40 years ago (71 percent today versus 85 percent in 1980) or to achieve financial independence (64 percent today versus 77 percent in 1980).

As male career prospects worsen, so do male marriage prospects, predictably. For now, women still seek a spouse who earns as much or more than they do.

For those who have been paying attention, this behavior is not caused by unexplained, sourceless apathy. As higher education has moved to a model which favors female strengths, men have been leaving it, and with it many of the higher paying jobs which require an advanced degree. For those already in the workforce, expanding H.R. departments—overwhelmingly staffed by women—and the politically charged sexual politics typified by the Me Too movement, have meant that formerly healthy male behaviors have been routinely coded as “toxic.” It is not an exaggeration to say that culture, writ large, has declared masculinity unwelcome. Men are being told to kick sand.

Are these men on the margins “Ken the way the girls would have him be”? Perhaps on its face, but female social behavior, especially in romantic relationships, suggests another conclusion. After all, men being “in their flop era,” as one Substack writer put it, is not an isolated problem. Indeed, for the vast majority of American women who hope to date and marry one of these males, the problem is theirs as well. Whether they blame male chauvinism, male inadequacy, or merely rising standards of acceptable relational behavior, women are incredibly vocal today about their dissatisfaction with the dating pool, yet unwilling to admit the causes.

Men, meanwhile, may be beginning to reject the paradigm. The response of young men to living in a Barbie world has been a mixed bag, especially on social media, with some following unsavory media personalities like Andrew Tate to embrace a kind of Hugh Hefner “masculinity” that consists more in flaunting material wealth and injuring women than any thoughtful critique of a world after feminism. (The Romanian government has charged Tate with rape and human trafficking.) More probing responses have come from online pseudonymous communities, like that on Twitter around the poster known as Bronze Age Pervert. While some of these reactionary personalities are better than others, and esotericism can make it hard to tell which is which, the women who critique them in magazines or TikTok clips are missing the point: The so-called manosphere exists because of an excess of feminine naysaying, and will not be answered by more of it.

In order to attract a woman and go the long haul, just focus on these following five questions:

- Do I lack purpose or drive? (Do I have a career I like that pays relatively well, or do I have a clear path forward to get me there?)

- Do I say no when I mean no? (Or do I say yes to keep the peace?)

- Do I communicate my needs clearly and effectively?

- Am I calm? (Or do I get easily agitated?)

- Am I in good physical shape, and do I pay attention to my appearance?

Men with purpose and drive don’t need to be rich; they need only be motivated toward something that lights them up. That will light her up.

Men who say yes when they mean no will not get the respect they crave. Always tell the truth, even when it hurts.

Men who communicate their needs are sexy. Men who clam up or stay quiet are not.

Men who are calm are enormously sexy. Men who yell are not.

Women aren’t sexually attracted to men who are lazy with their appearance. Put in the effort to be healthy and look good.

To reiterate: You cannot make a woman be less masculine. But you can provide the structure that will allow her to feel safe. And when she feels safe, she softens.

Right now we have a nation of women who don’t feel they can trust men because men have succumbed to the equality message just as fiercely as women have and as a result have taken a step back.

This is not what women want. I know it feels natural to do this as a result of women becoming more like men, but that is not the answer.

I know what I’m saying isn’t easy to hear or easy to do. I know that it feels easier to let women be men because there will be less conflict and because you’re so good at serving women, and it seems like this is what they want.

But it isn’t. Every week I hear from married couples that learned this the hard way.

So be preemptive. Don’t fall for the sexual equality garbage. That’s for the workplace, not for your relationship. Stay true to what God (or nature, if you prefer) made you to be: fierce and strong and purposeful and protective.

Male nature is the one and only thing that will cause a woman to surrender to her femininity, which will in turn create peace and passion in your relationship. If she won’t follow your lead, you’re either doing it wrong or she’s not the womanfor you.

Just stay focused on YOU. Forget about what women are or aren’t doing. As long as your answers to the questions above are no, yes, yes, yes, and yes, you’re in great shape.

If not, you have some work to do.